A Short History of the Irrawaddy Flotilla Company

(With kind permission of the Irrawaddy Flotilla Company)

The original Irrawaddy flotilla was a naval task force of paddle steamers and flats (barges) sent from India to transport British and Indian troops upriver in the Second Anglo-Burmese War of 1852. Unlike the First War, when the British were caught out by the monsoon, this war was a highly organized affair. Preparations in India were extensive and included the transfer of steam paddle ships of the Bengal Marine for troop transportation on the Irrawaddy. These were officered by British and crewed by lascars. Taking advantage of divisions at the court of Ava, the flotilla advanced rapidly up the river capturing Prome and then the prized Myede forests just above Thayet Myo. The British had never intended to hack off so large a chunk of territory, the original plan was to capture and hold Martaban, Rangoon, and Bassein – the important southern ports. However, the Province of Pegu, rendered defenseless by a government in turmoil, with its extensive forests and rich resources was to great a spoil. Interestingly, the commander of the naval operations (who died of illness on the river) was the brother of author Jane Austen, Rear-Admiral Austen. Meanwhile, at the capital of Amarapura, the King Pagan Min was deposed by Mindon who promptly negotiated a treaty with the British.

|

In 1864 the Governor of British Burma, Sir Arthur Phayre, decided to privatize the flotilla. After the cessation of hostilities it had been assigned to peacetime duties. Todd, Findlay and Co., a Scots firm established originally in Moulmein and latterly in the emerging capital of Rangoon, purchased the four steamers and three flats. As a sweetener the government guaranteed mail contacts but, given the poor condition of the vessels, Todd, Findlay, and Co. had nothing but trouble with them. However, the potential had been realized and in 1865 a company was formed in Glasgow with Paddy Hendersons shipping line, who were already in Burma with Rangoon a port of call on their New Zealand runs, and Denny’s of Dumbarton, the shipbuilders. This partnership of merchants, shippers, and shipbuilders was to offer a combined expertise and experience that gave the company an entrepreneurial thrust linked to a grasp of technology.

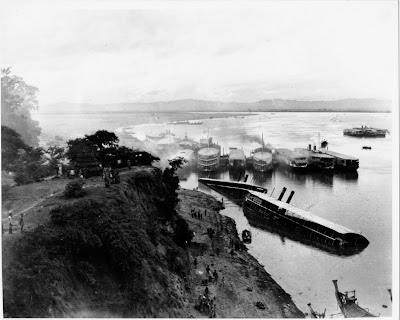

By the late 1860’s it proved necessary to replace the old government steamers and new vessels were built on the Clyde, dismantled and shipped out for reconstruction in Rangoon. It took some years and much trial and error though before the company perfected a design suited to the difficult conditions of the Irrawaddy with its perilous shallows. By 1872 the fleet comprised eight new steamers and twelve flats. Services operated between Rangoon and Prome in British Burma, in Royal Burma up to Mandalay, and by 1869 Bhamo. The company realized the importance of the China trade and saw the importance of a river link to South West China through Burma. Though King Mindon was said to have moved capital to Mandalay from Ava in 1855 out of irritation at the sound of passing steamers’ whistles, and despite efforts to establish a flotilla of his own, the company prospered in Royal Burma thanks to the close relationship between the company agent, Dr. Clement Williams, and the King.

In 1885 the flotilla was used in the 3rd Anglo-Burmese War to transport an entire army into Royal Burma to occupy Mandalay with scarcely a shot fired. For the following sixty years, until the Japanese invasion of 1942, the story of Burma, with her rise to great wealth and economic supremacy among the Asian nations, is intertwined with the operations and activities of the Irrawaddy Flotilla Company. Scots guile was quick to realize that Burma was a land of rivers and even with the completion of roads and railways the river remained the key to the riches of Burma.

By the 1920’s the fleet consisted of 622 units (267 powered), from the magnificent Siam class of 326 feet long (the same length as the height of the Shwedagon Pagoda) and licensed to carry 4,oo passengers, to pilot craft and tug boats. In a normal year the company carried eight million passengers (without loss of life) and 1.25 million tons of cargo. Irrawaddy vessels tended to have side paddles and would tow two flats, each lashed to either side. On the Chindwin, which was pioneered during Thibaw’s reign by company steam launch in 1875, a radical new design was created by Denny’s to cope with the shallow conditions. To balance the displacement, the paddle was situated in the stern and the boiler in the bow. This steam wheeler type would draw only 2.5 feet of water and, as the Chindwin valley was wooded, regular fueling stations were set up so the vessels did not need burden itself. The larger company ships had Scots masters and engineers and lascar crews recruited mainly from the Chittagon area, the lesser ones were entirely Chittagonian. The company had 200 expats based in Burma and a local staff of 11,000. Head Office was in Glasgow but in these pleasant phoneless and faxless days regional “Assistants” were autonomous. There was one telegram a month from Rangoon to Glasgow and that consisted of one line only – the total takings!

|

| A replica steamer of the 21st Century Pandaw Cruises |

In addition to passenger and cargo transport the company operated a fleet of oil barges to carry crude oil from the Chauk area to the Syriam oil refinery for the Burmah Oil Company. Paddy was carried for Steel Brothers on specially designed baddy boats and timer for the Burmah Bombay Corporation. The company pamphlet of 1935 describes produce carried:

“- great bales of cotton, bags of rice, blocks of Jade, lacquerware from Pagan, silk, tamarind, elephants, sometimes woven mats, maize, jaggery, bullocks, marble Buddhas, oilcake, tobacco, timber. Upward bound will be various imports from Europe, motor cars, corrugated iron, condensed milk, matches, aluminum ware, sewing machines, piece goods, soap, cigarettes, cement and whisky. Every class of goods that enters or leaves Burma finds its way onto an Irrawaddy boat.”

In 1934 the Irrawaddy Flotilla& Airways was set up offering scheduled services and charters – including an unusual service for devout Buddhists whereby an aircraft would encircle the Magwe Pagoda seven times. The passing of company steamers was part of river life and when the company changed steamer design and removed a funnel there was an outcry among the Burmese villagers. A 2nd dummy funnel had to be added in the interest of public relations.

The Irrawaddy is an untamable river – there are neither locks nor weirs to control the level as on the Mississippi or Nile – and in the monsoon the water level has an average rise of 50 feet (in the first Defile 200 feet). Nor are there charts, for the sands shift with such rapidity that they would be out of date before the ink is dry. Instead, the company operated its fleet safely end efficiently through the experience of her masters and pilots and a clever and inexpensive system of Bamboo marker buoys. Buoy Boats in charge of beats constantly checked and marked the channels with buoys and the bearings with marker posts on the riverbanks. If a captain went aground he had to stay with his vessel, in the case of the Momein in 1919 for a whole year. In 1877 the Kha Byoo was caught in a whirlpool in the second defile between Katha and Bhamo. She spent three days spinning in a circle before getting free and the captain’s hair had turned white.

The captains lived on the bridge and many of the river features were named after incidents they experienced at their hands, thus there was “Becketts’s Bluff” or “MacFarlane’s Folly”. Scott O’Connor best captures their proud commands:

“Some of the steamers that come this way are of the largest size; mailers on their way from Mandalay; cargo boats with flats in tow, laden with produce of the land; and when they come round the bend into full view of Maubin, the great stream shrinks and looks strangely small, as it if were overcome by a monster from another world. Three hundred feet they are in length, these steamers with flats in tow, half as wide, and they forge imperiously ahead as if all space belonged to them, and swing round and roar out of their anchor chains, while the lascars leap, and the skipper’s white face gleans in the heavy shadows by the wheel – the face of a man in command.

And when you see this wonderful spectacle for the first time, you step on board this great boat expecting to fin an imperious man with eyes alight with power, and the consciousness of power, and the knowledge that he is playing a great part. But you are disappointed, for you find a plain man, very simple in his habits and ways with weariness written about the corners of his red eyes. Ah! They know their work, these men…. And I say nothing of the Clyde men who rule the throbbing engines…’ Silken East, 1904

The story of the Irrawaddy Flotilla is a story of Scottish-Burmese partnership. As the yards on the Clyde where these great ships were built stand silent, so too do the yards of the Rangoon River where they were once reassembled. In the first part of the last century two dissimilar nations established a rapport and shared a prodigious wealth that neither country had known before or since. The demise of the flotilla was perhaps the saddest day of British merchant marine history; when else have six hundred vessels been lost in one fell swoop? That swoop was neither natural disaster nor enemy action, but at the hands of the companies own officers. In 1942, before the oncoming of the Imperial Japanese Army, following the evacuation of Rangoon and escape to the upper river, they gunned holes in the great ships’ hulls rather than let them fall into enemy hands. It was called an “Act of Denial”.

You must be logged in to post a comment Login